One of the most alarming things about our age is the sheer volume of information we’re exposed to. The world has always presented itself as an excessive too-muchness, but what has changed is the way in which this too-muchness shows up for people tangled in the world wide web. Being itself is obliterated, in a sense, as everything gets recapitulated and represented as a data stream. Life becomes a movie, a show, or a presentation. The seeming begins to overwhelm what is.

Such an entanglement in wires and signals is a poor substitute connection to reality and even to ourselves, but we may get distracted enough that we don’t even notice this. The complex or memeplex overwhelms the shining-forth of phenomena. It becomes difficult, therefore, to tell the difference between satire and journalism, for instance, as the values structures in society become more and more incoherent. This is just one result of being embedded in the flow of constant information. It is difficult to know exactly what we should value.

Once upon a time, when we didn’t know something during a dinner conversation, we just didn’t know it. If we didn’t know it, maybe it wasn’t that important. Ignorance was once permissible, as difficult as that may be to believe nowadays. Until recently, in fact, a person wouldn’t reach for the nearest electronic device to find out what he didn’t know—because he couldn’t. Such intrusions into life hadn’t been invented. In any case, that was not the primary way of knowing the world. We know the world by being in it, first; by participating in it, not by having data on it. We know others not by liking their selfies or conducting online interviews via video chat but by being in their space. We know things by dwelling with them, not by doing a Wikipedia search on them.

But now a person doesn’t even have to be plagued by a question to go searching for an answer. Nowadays, you can hardly go five minutes before being given an answer you never even cared to be confronted with. It seems to me that without a resonant question, answers are likely to feel hollow. And the truth is, any question that presents itself as expecting yet more data is really a degraded question—it is not going to allow for the kind of answer that would truly satisfy. So, well, forgive me for repeating the obvious but it’s not for no reason that the age we live in is called the Information Age. It’s a time marked by a massive and still accelerating shift from traditional industries established by the Industrial Revolution towards an economy rooted almost entirely in information technology. As we move away from tradition itself, we’re left decontextualized.

Note the centrality of economics in how this Information Age is defined. Etymologically, the word economy comes from the Greek oikonomia, meaning household management. This etymology has comforting overtones. What could be lovelier than keeping your home in good order, like Marie Kondo organizing spaces to welcome calm in a world of overwhelm? However, as Girardian scholar, Jean-Pierre DuPuy has pointed out and as the rise of crypto-currencies confirms, the economy—this impersonal realm of exchange and transactionality—is entirely mimetic. It is mimetic, I would say, in two senses: at the level of how desires breed asexually, as well as at the level of being obsessed with surfaces. Value is no longer regarded as intrinsic but is now predominantly a matter of consensus and contagion. Value is now data-driven. The economy now amounts to a kind of perpetual chaos out of which an occasional pattern may emerge. In this mimetic flow, order is more of a bug than a feature. It is an epiphenomenon more than it is a phenomenon. We are no longer in household management but are instead simply riding the chaos.

So, here we are, with this overwhelming abundance of information, and it is an abundance that coincides with a global crisis of meaning—the rise of nihilism. This started long ago but it doesn’t appear to be getting much better. Whether we are dealing with correlation or causation, or a mix of both, the pile-up of information can’t be separated from hermeneutical impoverishment. Add yet, what Viktor Frankl calls “the will to meaning” is inescapable. We somehow must make sense of the world even when we can’t. We will search for meaning even if we are convinced that everything is meaningless. Meaning, then, seems to be something intrinsic to being. The universe is made not out of stuff but out of meaning.

And this inescapable need for meaning, I believe, is part of what has generated the rise of memes in the Information Age. The will to meaning has given rise to the will to meming. We know, of course, that the idea of a meme was coined by Richard Dawkins in the mid-1970s to describe bite-sized units of cultural information analogous to genes. Since then, the term’s meaning has shifted slightly. If it was once, to quote the Oxford American Dictionary, “an element of a culture or system of behavior passed from one individual to another by imitation or other non-genetic means,” it is now more commonly understood, to quote the same Dictionary, as “an image, video, piece of text, etc, typically humorous in nature, that is copied and spread rapidly by internet users, often with slight variations.”

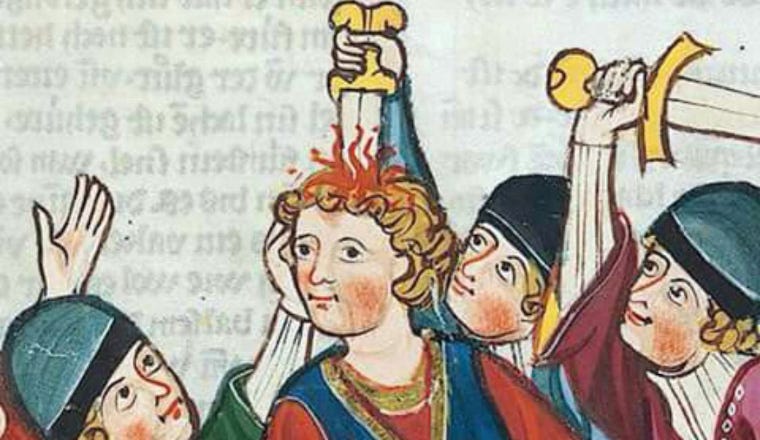

It is such memes, reflective of this latter definition, that I want to briefly discuss here. I realize that this may seem like a trivial topic of conversation that no one should really contemplate. However, the sheer prevalence of this form of vernacular creativity should be enough to suggest that there may be more to memes than we may initially notice. Still, it’s helpful to begin with the obvious before going deeper. What is obvious, for starters, is what the above definition suggests. Memes are predominantly the result of digital culture, born and bred within a simulacral sphere. Apologies for stating what you already know, but typically a meme begins when one image or a series of images is or are taken out of context and then remixed to create new meaning. The key here is to see memes as essentially intertextual, to use a term coined by Julia Kristeva.

Intertextuality has become synonymous with the postmodern condition. The basic idea is that one text could, either deliberately or accidentally, refer to other texts. For the record, text here doesn’t just mean written words only but refers to any human creation; it could be an object or image, for instance. Intertextuality, then, may just be a fancy way of referring to allusion or influence. The basic idea is that the meaning of an immediate text is significantly shaped by being connected in the mind of the reader to other texts. The allusion to other texts has an impact on how the immediate text is interpreted—and this will also affect the way we interpret its source texts.

There are various ways to manufacture intertextuality. Quotation, plagiarism, translation, pastiche, and parody are all examples. The meta-level is a vital dimension of this. That prefix, meta, stems from Classical Greek; it means with, across, or after. We find the idea of the meta in words like metaphysics, metabolism, and metaphor. As the idea of the meta would suggest, the key to understanding a meme is having a sense of the contexts it is derived from; there is seldom only one context at work. The tendency in meme-creation, as in all jokes, is to smash two or more contexts together to see how they interact. It’s this combination of contexts that generates much of the humor.

Let’s take the famous Condescending/Sarcastic Willy Wonka meme as an example. In the 1971 movie, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, the actor Gene Wilder is about to introduce his most secret machine. To create playful suspense, the actor strikes a pose. This pose has been screengrabbed and yanked out of context: the result is that what looks like playful suspense now looks like sarcastic condescension. Words attached to this image typically follow this mood, and part of the fun is found in the fact that it deliberately misinterprets the context. If you don’t know the context, chances are good that you’ll catch the condescension but miss the joke. Of course, now that I’ve explained the joke, it definitely isn’t funny anymore.

As this implies, memes tend to foster something like an awareness of what’s going on. They create a gap or distance within the totalizing sphere of information. They don’t just allow for but require a measure of reflective distance. To resonate with any meme, even just a little, you have to know more than what is immediately apparent. To get the joke means knowing more than what the joke is actually saying. Moreover, the wider and greater your awareness, the better the chances of finding resonance. This is symbolized by the predominantly visual form that memes take. Yes, there are memes that incorporate audio, but most of the time, it is the visual nature of the meme that does the trick. As McLuhan noted, visuality generates the illusion of a chasm between the subjective and the objective—a gap that phenomenologists are well aware doesn’t exist in reality. It is an imaginary gap, albeit an often useful one.

In this meme-made awareness is another vital dimension of memes. They tend to be built on pattern recognition and pattern-creation. You can’t joke unless you see patterns. You can’t make meaning without perceiving patterns either. And you can’t see patterns without awareness. Many memes, like the ‘Anakin and Padme’ or ‘guy turning head’ memes, set up an awareness of a specific structure or relationship. This is what makes the jokes work. Again, there is something vital to this mode of meaning-finding and meaning-creation. As an extension of the way memes encourage awareness, this pattern recognition highlights the essentially relational nature of our search for meaning—through meming.

There is also a pervasive sense of critique in meme culture. Humor often involves critique, and so it’s no surprise that the awareness fostered by memes tends to be of a critical nature. The Information Age is notoriously humorless, so it’s wonderful that this jovial joke-wielding culture has come about. I’m sure you’ll agree that we all desperately need, from time to time, to not take ourselves and the world too seriously. But here, in this very good thing, we might start to notice hints of something less than ideal, where memes can fail to lead us onward towards real meaning. In this, memes become a substitute for meaning, rather than indications of a search for it.

The focus on a breadth of meaning in memes can be, and often is, at the expense of depth. The attempt to generate awareness is momentary. I think that the prevalence of critique in memes sets up the possibility of what Robert Pfaller calls ‘illusions without owners’—where critique becomes a way of disowning one’s own situation within the world. The meme easily mocks, but seldom affirms. There’s an analogy here to some forms of schizophrenia, where the possibility exists to view life as a mere game; such a schizophrenic stance can be so detached from life that it cannot imagine regarding any specific task as real. There’s a struggle to connect emotionally. Everything can seem unreal, trivial, and inconsequential. Thus the will to meming can fall backward into a will to nihilism, against a will to meaning. Well, that danger exists here. We know that the internet is obsessively constructivist—generating meaning horizontally through structural repetitions and variations. But in all of these signifiers there is often a loss of referent (to use the language of semiology).

What does this mean for life? Well, the trouble is that meming’s meaning tends to function at the level of tickling the mind without necessarily resonating with the heart or the body. I found this to be particularly evident in the latest installments of the Matrix and Spider-Man franchises, which had plot points built almost entirely out of meme-like structures. The stories feel imposed, rather than being natural arising out of the worlds that the characters inhabited. Spider-Man: No Way Home has been very well received by critics and audiences, but it left me feeling rather irritated. The Matrix Resurrections movie was catastrophically stupid, but let me focus on Spider-Meme here. Ah yes, there’s a Spiderman multiverse meme out there, too, isn’t there?

In that film, a strangely un-Strangey Doctor Strange flippantly casts a spell that goes very, very wrong. Then, suddenly, all the previous recent Spider-Man movies begin to leak into the most recent one. Enter the multiverse. Here we have a clear sign of the way that narrative has collapsed in our time, only to be replaced by an incoherent string of pings and notifications. Ping! Look, an old villain from that previous Spider-Man movie is here! Ping! Look, here’s whatshisname from that not-so-great Spider-Man movie I was kinda hoping to forget. Ping! Oh, no! Another Spider-Man from another Spider-Man movie!

We have been well programmed by the digital equivalent of Pavlov, it seems. I was not so impressed—and I speak as someone who actually enjoyed the previous Tom Holland (the actor, not the historian) films, which felt like they at least had some sense of narrative coherence and character depth. Clearly, however, I was in the minority in being disappointed. I heard whoops and gasps in the audience every now and then when someone from some other movie showed up, the way an audience of fans cheers when a guest artist shows up unexpectedly on a stage to support the main attraction. In those moments, while watching the film, I had a terrible sense of foreboding. Our current crisis of meaning may be worse than I thought. Mere repetition (and the recognition of the familiar) is often a sufficient substitute for meaning these days. If films built on memes do so well, there’ll be more of the same. Oh dear. This is potentially what memes signal, even if memes themselves aren’t to blame for it: mere semiotics has replaced depth.

In the Spidey-Verse especially, but in meme-culture more generally too, there is one final warning that I’d like to mention. It is the warning of an implicit egotism in meming. What the No Way Home movie indicates, especially in its success, is a surreptitious tendency to make things ‘for the fans’—that is, to create not what has its own intrinsic value but rather that which signals to the audience that they are in the know. Already in being critical so often, humor risks conforming to the so-called superiority theory of humor. Often laughter is derisive: it can and often does result from a feeling of superiority. We laugh to mock the other, to look down on those who don’t conform to our ‘knowing.’ Well, in a culture of memes, this sense of superiority is often, if not always, echoed. It is a strange kind of superiority, though. It knows widely but not deeply. It feels, sometimes, like the people trapped in the cave that Plato described, laughing derisively at those who have been freed from seeing only shadows.

To laugh derisively, however, is not genuine laughter. It is not very deep. It sometimes resembles the whoops and cheers you hear when people see someone in the opposite team mess up. And here I sense the potential of memes to fail in their pursuit of meaning. Yes, they can and often do signal awareness, as well as an ability to somewhat escape the clutches of an ideological stronghold or a digital vacuum. But there is interpassivity there too (an alternate way of expressing Pfaller’s idea of ‘illusions without owners’), as well as a tendency to find oneself only momentarily freed from the constant stream of information, information, and more information, before getting sucked right back into it immediately afterward. Memes, like the pings, are not prayer bells but indications of being stuck in a vortex. This, to my mind, is the natural pitfall that must result from a mode of thinking that works pretty much at the same level as the very meaning-crisis it is trying to escape from.

This is not to say that enjoying memes spells doom. Let’s not get carried away. Of course, it doesn’t! It’s lovely to share memes with friends and family, and arguably most of us enjoy not only these global in-jokes themselves but also the way they remind us that we’re part of something; that we’re somehow all involved in the same world of meaning. Most of us experience memes as things shared, and it’s not meaningless that we do, in fact, have so much to share. Nevertheless, I do think it’s necessary to flag how we can nurture some of the wrong things in our sharing if we’re not careful. One mode of awareness, after all, doesn’t necessarily generate the depth of awareness that we really need to experience meaning in life. One kind of sharing is not the same as another.

And not all meanings—and also not all memings—are equal.

This was a welcome surprise in my inbox. I’ve consistently enjoyed your writing.

Memes have been a topic of my own musing lately and you pinned down very similar conclusions as mine. I remember when the RSA animate videos first came out around 2009 and I would be transfixed by watching sometime visually transcribe on a whiteboard, what a lecturer was talking about. There was something absolutely mesmerizing about seeing the words of a lecture pass into a visual story of the artists direction. It felt that it made the ideas more understandable to see them presented as images. I think memes act in the same way, providing a visual, condensed form of ideas, often jumping over the gaps of literacy, presenting packets of meaning to all who have enough time for a glance.

They are also a sign of our inherent desire for shortcutting. To present everything all at once. “Just present the Meme and I will be healed”.

I had never considered the insider/outsider dynamics of memes, but now I realized that there are definitely some memes I won’t send to my parents and others I won’t send to non-Christians. And on the other hand there are memes that cross boundaries and present ideas that can bring others along into different ways of thinking without them even knowing it. It’s a dangerous kind of sorcery on one level and a providential way of spreading Truth on another...

Brilliant. One of the joys of life to me is always in ambiguity - in a meme, a sermon, a photo, a piece of iridescent fabric, or a glimpse from the corner of my eye. In recognising that we can’t nail down definitive meaning keeps my sarcasm and cynicism at bay, but the quest is always there.